One dictionary defines “capacity” as the innate potential for growth and accomplishment. In the world of leadership, having capacity is a necessity; it is a key to successful leadership and a successful organization, whether that be the union hall or the church or the family or the family business. Without capacity there is stagnation. And for those dependent on another’s capacity, a lack of it creates profound frustration.

One dictionary defines “capacity” as the innate potential for growth and accomplishment. In the world of leadership, having capacity is a necessity; it is a key to successful leadership and a successful organization, whether that be the union hall or the church or the family or the family business. Without capacity there is stagnation. And for those dependent on another’s capacity, a lack of it creates profound frustration.

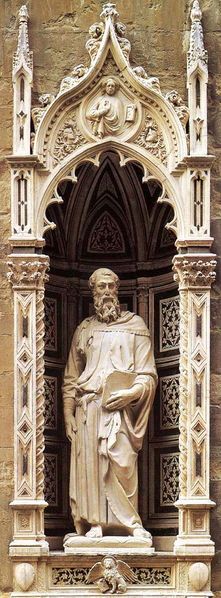

John Mark was an historical character whose story plays out in the New Testament. And he was a man whose early lack of capacity gave way to a tremendous measure that has influenced the ages. Consider the following.

We first meet Mark in the gospel account that he wrote, but our introduction to him is not necessarily as the author, for he never formally introduces himself. It is, rather, as a very vulnerable man in the Garden of Gethsemane. When Jesus was arrested on the night of his betrayal, utter chaos broke out, and the disciples, one after the other, took off running into the night. Caught up in this melee was a young man who had followed Jesus into the garden. I am personally convinced that Jesus and his disciples had eaten the Passover meal at the home owned by this young man’s mother, a woman named Mary (see Acts 12:12 for additional background). If I am correct this young man is named John Mark, or commonly, Mark. The gospel account focuses on him in this way: And a young man followed Jesus, with nothing but a linen cloth about his body. And [the arresting soldiers] seized him, but he left the linen cloth and ran away naked (Mark 14:51-52). What a most unfortunate introduction.

The next time we see him is in Acts 12, when reference is made to his mother and their home, which evidently became the nerve-center for the early gathering of Christians. We become aware of this because when the Apostle Peter is jailed and then sneaks away by God’s merciful help, he makes his way to Mark’s home. The text offers: When [Peter realized he had been set free] he went to the house of Mary, the mother of John, whose other name was Mark, where many were gathered together and were praying (Acts 12:12). One thing that is evident in the verses that follow is that Mark’s family must have been wealthy enough for them to have servants (see Acts 12:13) and have enough room for many to gather (consider too the likelihood that Jesus and his disciples gathered there for their final Passover).

The synergy which was life in the nerve-center of the early church was such that Mark clearly caught the attention of the leaders, men like Barnabas and eventually the Apostle Paul. Thus it was that when Barnabas and Paul set out on their initial missionary journey, they took Mark with them. Clearly both men sought to invest in Mark, and also sought to benefit from what they perceived Mark could offer. Unfortunately, they were to be let down. Mark lacked the capacity to pursue the journey, turning away and returning home, as recorded in Acts 13:13-14. Mark’s exit from the mission clearly frustrated Paul, and Paul was to not forget it. Some time later, when Barnabas and Paul had opportunity to strike out again on another missionary endeavor, Barnabas, wanting to give Mark another chance, recommended him to the mission, but Paul refused. Acts 15:38-39 declares that “Paul thought best not to take with them one who had withdrawn from them in Pamphylia and had not gone with them to the work. And there arose a sharp disagreement, so that they seperated from each other.” It is with this relational fissure that Barnabas heads out on his own, with Mark at his side. Paul goes in an entirely different direction.

And then we have silence for many years, until, much to our surprise, the Apostle Paul references Mark in some of his letters written from Rome (see Colossians 4:10; Philemon 24). It is evident by such notations that somehow or another Mark reconnected with Paul, and Paul must have invested himself into Mark’s life. These years found Paul in prison, so Mark’s presence must have been significant. Indeed, by the end of Paul’s life Paul could write from yet another prison experience—one from which he would be led to death—that Mark “is helpful to me in my ministry” (2 Timothy 4:11). What a turnaround from Paul’s rejection of Mark many years prior.

But Paul and Barnabas were not the only leaders with whom Mark spent time. The Apostle Peter also invested a great deal of time into Mark’s life. Thus he writes in 1 Peter 5:13, when offering a greeting, “She who is in Babyon, chosen together with you, sends you her greetings, and so does my son Mark.” This is an important detail, for tradition tells us that much of the Gospel of Mark is heavily influenced by Peter’s eyewitness accounts of Jesus’ life. One can imagine Peter sharing story after story—perhaps in sermons or in private lessons—and Mark captured these things in his mind and heart. If this is so, then the breadth of the Gospel of Mark would suggest that Mark must have spent a lot of time with Peter. Peter’s detail that Mark is like a son speaks to the mentor/disciple relationship they clearly had.

And then the likes of Paul and Peter are gone—executed in the mid-60s in Rome under Nero’s rule. With those sagacious leaders out of the way, to whom did the fledgling church in Rome turn for guidance? Tradition tells us that the Christians in Rome turned to Mark. And with Nero’s persecution of the believers being so brutal, I suspect they turned to him with urgency and great fear, asking him, in effect, to answer one simple question: in light of the fact that the Romans are killing us off, is this Jesus thing really worth it?

To answer that, Mark wrote the gospel that bears his name. And millions have benefitted.

Obviously, the somewhat spoiled young man whose lack of capacity caused him to leave his commitment to Barnabas and Paul increased his capacity and ultimately was used to help change the world with his gospel account. But how? What ingredients would contribute to Mark’s development? How did he move forward, gaining capacity, growing and accomplishing things as he eventually did? As I survey the story of Mark’s journey six ideas come to my mind. Consider the following formula:

Time (many years passed from his return home to the time when he wrote the gospel account; perhaps as many as twenty years), plus tough stuff (it must have been shameful to leave Paul and Barnabas and return home, only to later be rejected by Paul and bear the hurt of contributing to the fissure between Paul and Barnabas), plus teachability (Mark must have come to a place of getting over himself enough to want to learn from Barnabas and then Paul and ultimately Peter), plus the right teachers (one could hardly get better than these three sages who invested in Mark), plus tenacity (Mark’s fast-paced narrative that bears his name may well be a great indication of the tenacious spirit this man developed, a determination to become something better), plus a test (the urgent request to step into the sandals of Peter and Paul and rally the church through its intense suffering) in which to prove capacity, gave way to a tremendous measure of power that transformed the early church and the millions of Christians who have read his work.

Time + tough stuff + teachability + the right teachers + tenacity + a probing test help develop capacity. It is worth asking if these things are found in your life and the lives of those around you. If not, they may well be six things you need to embrace.

* * * * *

“Write This Down…” provides a restatement of selected points or observations from various teaching venues at which Pastor Matthew speaks. The preceding material is from Pastor Matthew’s message entitled, “The Leader and the Power of Great Capacity,” and presented at the Fargo-Moorhead PowerLunch on December 8, 2011 at Bethel Church.